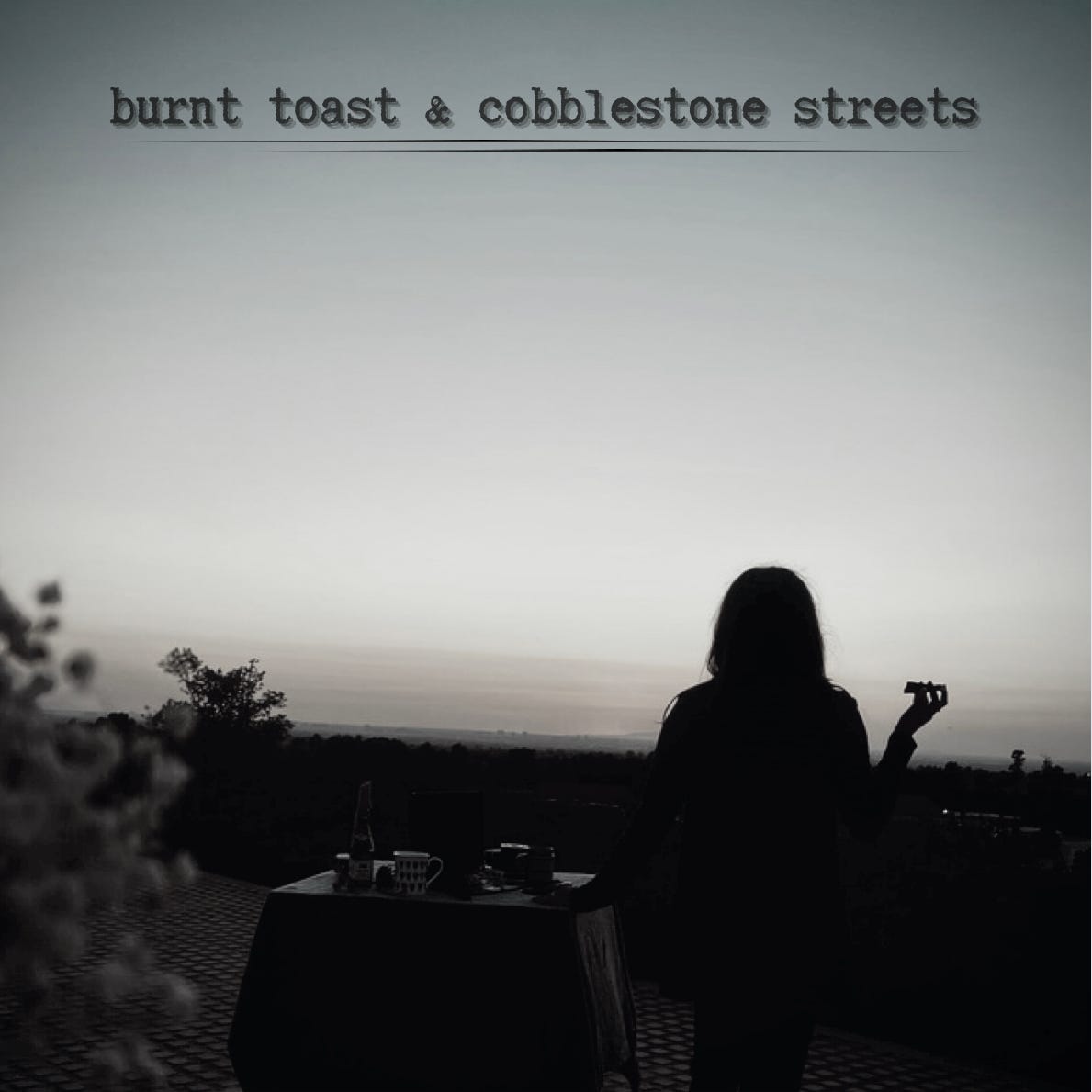

My mother had exquisite hands.

Like finespun gossamer.

When I extol the virtues of her hands, like those of a mother gripping her seat mid-flight in a scene of my novel, I find language alone deficient — beggared and hollow. My mother’s hands were meant to grace poetry books and bone china teacups, arrange floral displays on glass tables, glide through waves of golden-brown, and twirl to baroque waltzes made-believe between the walls of one’s bedroom. Held against any light, on any day, by any convention and every standard, I’d argue my mother’s hands eclipsed them all. Well-manicured, always lacquered, slender and unlined, with delicate, beringed fingers. Dignified in movement. Unaccustomed to labor.

My mother’s hands were a story untold.

[copywrite Nasha U. Khan]

In recent years, I’d avoided looking at my mother’s hands. Or maybe I’d just stopped noticing them, as I incline to with all unmendable things. Not nearly on account of her deformative arthritis however, as one injudicious email described to unknown and unrelated ilk, upon news of her passing — on behalf of her unsuspecting children, of course. As if such grotesque attention to this gratuitous detail could explain away her sudden death. Or justify her road’s end. Ah, I imagined the readers sighing, makes perfect sense — as an image of the gnarled branches on a contorted beech tree crept across all memory of the tapered alabastrine of the more elegant Japanese white birch. “Deformative arthritis” can, for some, be a death sentence I suppose.

Not my mother though. The bony spurs twisting her fabled fingers were no match for her dexterity and grit. Will I be able to use them still was her only response to the corrective surgery question when they first began curving. What good are beautiful hands if you cannot use them?

What good indeed.

In spite of her rheumatic condition, returned 15 years post-remission, she’d continue to use them just as she had before. Even when the foaming vengeance would replace her days of handling fistula cannulas by day and cash registers by night with ostensibly more befitting hours — playing counselor to irreverent youth and editing a thankless publication for literary heathens. Roles she’d embrace in a life that thickened the blue blood of her crested past into the crimsoned sludge of the working woman. Through the relentless pain, managed with pressure bandages to “avoid all these medications” that would indeed one day ravage her. Her angled fingers slipping beneath the compressions to grip, grab, hold, and serve the things and people that made up her life — until her limbs and mind would betray her. Only to return one last time to what she’d known — her empathy and love, her constancy, her art. Reminding me, my children, and my father, perhaps, of what her hands in all their avatars had done.

So began the 19th day of Ramadan.

Despite their beauty and dogged utility, my mother’s hands never amounted to much — languishing alone in unrealized potential’s crumbling neighborhood. Her poetry and brilliance obscured into the dulled pages of piling notebooks and sketchpads. Her labor and creativity burrowed into the forgotten margins of an untitled dastaan. All that talent, I used to think, will turn some day to dust.

I didn’t inherit the grace of those hands, but their gifts did trickle into my own. And I willed myself into believing I wouldn’t go her route. I would occupy every space, blow past barricades, explode my art into the world. That’s how I’d make this life not hurt.

A part of me wanted to show up for my father and her just so I could hold up my prize — all the stories of us — and say, “Look at what our pain has borne.” As if it would make up for what we lost. Just you wait, I’d think. I will make this count.

But grand gestures are sometimes all for naught.

On an early spring morning one day, just as the sun breached the horizon, I found myself looking upon my mother’s dying face — laying waste to all gestures.

So began the 19th day of Ramadan.

My mother and I had a complex, at times fraught relationship. First daughter/middle child syndrome, opposing personalities and dispositions, childhood traumas and neuropsychiatric conditions, caregiver burnout — whatever the reason, the list grew unabashedly long, leaving grief as the only residual constant.

At the surface, we couldn’t be any more different. She with her gentle, submissive, accommodating nature and I as the temperamental ogre lumbering about with my signature grimace scaring away all creatures. But my impatience with her, I often reflected, arose from the acute and unwelcome recognition that she was the embodiment of what I considered my weaknesses.

In this insatiable capacity to love, its reciprocal need to be loved in equal measure, and the failure to withstand the impossibility of such expectation, we were perhaps more alike than not. Every path we took led back to this place of wanting for us both. Except where I drew back, erected brick walls, locked doors, and bolted windows, she — no matter how brutally battered — seemed determined to let in anyone who wanted to walk through her door.

They don’t care about you, Mom. Why don’t you get it? My voice would rise through tears during heated arguments. I won’t get it, Nasha. This is just how I am. She’d yell back, ringing her broken hands — the small, fragile knuckles turned into knobs of bony excess, her once perfectly-shaped and varnished nails now masticated and brittle.

Somewhere across the 15 years of winding along the many paths in and out of her reality — that chose her mental presence and absence at will — against all wish or design, my mother and my oft-charged relationship had redefined. And with all the maternal protectiveness I could muster, I came to guard fiercely my unloved, troubled child.

But I was wrong.

This was made plain the day she died, and the weeks that followed closely behind. The silence of the years before hadn’t been an accurate judge at all — as the masjid she’d frequented, in some part redesigned, and that held her janaza prayers overflowed with people whose paths she’d crossed. The local gossips and nouveau-riche wives, the community center cooks, the old security guard’s children, the staple grandmother at parties stationed on one end of a couch, the troubled teenagers questioning their identities, the young men and women who’d long ago frequented our house, the social-climbers, the widows, the divorcees, the relatives and friends who’d forgotten her, the ones who still called — her once irksome habit of befriending anyone and everyone she’d ever met had now brought them all back to her door. I realized in those moments, as I absorbed their words, that my mother’s most redemptive quality lay not in her strength or her resilience or even her steadfastness when things got unfathomably, unbearably tough. It was in the way she made people feel — like they were the most important person in the room. And though human memory is uncharitable and short, my mother with all her troubles was loved — deeply loved — by all.

It’s always the obscure details that remain when the dust settles, I’m told. But I remember every scene, every note, every second of my mother’s final curtain call.

I remember her panting up the steps in the blue polka-dotted pajamas I’d bought her last summer — to ask me another question for which I had no answer. The understanding smile in her expression that I hadn’t seen for me in years. And the shift between us, a softness I’d thought long lost. I remember her familiar frame in bed that evening, reading, with two pillows propped behind her. Glasses perched on her nose. Her perfect profile. And her face — luminescent and youthful once more. The cruelty of time suddenly disappeared. I remember our animated chatter after dinner. The laughter filling our home. And the strangeness of the night as I stayed up with my children past bedtime, sharing stories that somehow involved mostly her.

I remember how swiftly the tranquil quiet turned into chaos as I searched for signs of life in her with the due diligence of the steady workhorse. And the delay in the rise and fall of her chest that dawn — so different from the way it did when I stood at her doorway in the dark. I remember my one hand cradling her neck, the other over her, holding her close. And the weight of her still body as a familiar, mothering voice — gentle, firm, foolish — filled my ears. Open your eyes, Mom. I’m here. You’ll be okay, Mom. I’m right here. Don’t worry, Mom, I’ve got you okay? I’m here, Mom. It’s okay. I’m here. I remember my fingers pulling at her lids, and all that vivid green transfixed — on me, through me, beyond me — to something unknown. How soft her skin felt. And then how cold. I remember the faint pulse between us — not knowing whether it was mine or hers. Watching a second shallow breath escape. And the moment I felt that spiteful nothing under my fingers.

I remember details I’ve written and unwritten a hundred times, repeated in my head a thousand more. Details that, if propriety triumphs, will eventually settle between other things I’ve guarded from this curious, unforgiving, algid world. But mostly I remember her hands.

Those beautiful, brilliant hands of my childhood — that stitched the lavender’s blue dilly dilly gown behind the mirrored cupboards, and taught me to cross my fork and knife when I paused or parallel to indicate I was done. That sketched and drew in perfect measurement the rooms of imaginary homes she never got, and traced her name in homework diaries and school reports. That massaged warm coconut oil into my scalp, and caressed my head as only she could when I stirred. That held my death grip as I labored in blinding pain when no one else was home, and held my babies close. Their grace and dignity, capability and originality, their folded humility and willingness to serve, their ability to love in every weather, and their brave defiance as they bloomed and wilted in all the seasons of her.

And in death, she remains the most unreliable narrator wandering my head by far

My mother was no martyr. That I know. If she sat her sorrows on those treasonous bones, in her beaten hands she carried the afflictions of an entire world. Between the trials and illnesses that tormented her, and the systems and people who failed her — even I, who in the end, relinquished what I’d known of her, she in life absorbed the tenebrous shadow that pursued her. And in death became the most unreliable narrator wandering my head by far — pulling me up every day, then under. But nothing — no tragedy nor affliction, no flaw nor shortcoming, nor anything I say or write — captures the luminescence, the gentle brilliance, the otherworldliness of my mother.

My Mother’s Hand by Hattie Howard

How oft my burning cheek as if By Zephyr was fanned, And nothing interdicted pain Or seemed to make me well again So quick as mother’s hand

My mother had ethereal hands.

Like something that never quite belonged here.

But though I can no longer hold them, when I look around my life, the one I once lived with her, I see in it all the seeds her hands have sown.

Here they once again slice fruit for my father, just the way he likes it, into a bowl. Here they examine two identical swatches of material to be sewn for her girls. Here they hold a No. 2 pencil over a sheet of silhouettes she says resembles one of us. Here they swiftly thread a needle through the new sewing machine to embroider my baby’s first Eid clothes. Here they arrange wedding gifts, between gilded fabric, in baskets for a son or daughter. Here they stir the ladle in a pot of curried stew against a noisy backdrop. Here they lather a small, resistant head through soapy bubbles. Here they linger over another crossword puzzle. Here they clutch my sister’s tiny trusting hands as she steadies her own heart. Here they wipe my brother’s tear-stained cheek as her eyes blur. Here they twirl freely as she dances alone to music only she hears. Here they turn another page of another book, and steer another wheel into another turn. Here they pour water over her wrists and wash behind her ears. Here they pull over her hair the black khimar. Here they are fists that never open to catch her fall. Here they fold into themselves as I gently rub the kafūr — across fingers and knuckles and palms that will disintegrate into the waiting earth.

Here they rest until I find the way back to her.

For my mother (allah yarhama) with her quiet strength, who showed me the power of forgiveness and the ability to keep loving even those who couldn’t, who fought so hard to live, who filled my childhood with books and music and wonder and magic, who I carry in my every breath every day, who I wait to meet once more in a much kinder and gentler place than this bruised and bleeding world (ameen).

GLOSSARY

dastaan | urdu

/ dāstān / داستان /

n. / farsi origin / also urdu (farsi derivative) / from Central Asia, generally centered on one individual who protects his tribe or people from an outside invader or enemy.

fable, story, tale; an ornate form of oral history

Ramadan | arabic

/ ra-ma-dahn / رمران /

n. / arabic origin / from the root ر م د (ra•ma•da) / “the hot month” from ramad (intense dryness, parched)

9th month of the Hijri (from Hijra or migration) and lunar calendar in Islam; month in which Muslims fast from sunup to sundown;

masjid | arabic

/ mas-jid / مَسْجِد /

n. / arabic origin / from the root س ح د (sa•ja•da) / also urdu (arabic derivative) / roughly translated in English to mosque (mos•k)

place of sajada (to prostrate); covered space or facility for Muslims to pray and worship;

janaza | arabic

/ ja-nā-za / خمارة or جِنَازَة / jināza

n. / arabic origin / from the root خ ن ز (ja•na•za) which means “to wrap,” or “ to prepare a body for funeral” / also urdu (arabic derivative) /

funeral for Muslims; bier; corpse

Eid | arabic

/ īd / عيد /

n. / arabic origin / aramaic roots from ‘ed meaning day of assembly

festival; feast; day of feast; Islamic celebration;

Eid al Fitr (festival of breaking the fast, falls on 1st of shawwal 1 of the 10th month of the Islamic calendar); Eid al Adha (festival of sacrifice, falls on dhul hijjah 10 , the 12th and last month of the Islamic calendar)

khimar | arabic

/ khi-mār / خمار

n. / arabic origin / also farsi / from the root word خ م ر (kha• mīm• ra) which means “to conceal or to cover’.

anything by which a thing is veiled; for Muslim females, a scarf or veil and/or anything that’s part of their awrah (what needs to be covered from public view); for Muslim males, any garment that covers everything that’s part of their awrah (what needs to be covered from public view)

kafur | arabic

/ ka-fūr / كافور

n. / arabic origin / camphor in english

white transparent waxy substance (crystalline isoprenoid ketone) with a strong scented smell; used in Islamic burial ritual to reduce the smell of the body and delay the process of decay

Thank you for your indulgence. Stay tuned for a full essay podcast.